Fluorescence

C. elegans study requires a particular aproach. Being a transparent and small animal makes imposible its study at microscopic level in the usual way. Instead dyes that under the correct light (wavelength) emit fluorescence in an intensity level, are used.

Using this technique is posible to acomplish a great variety of studies with different dyes, filters and lighting techniques.

Two of the most performed studies are neuro-muscular and lipids inspection.

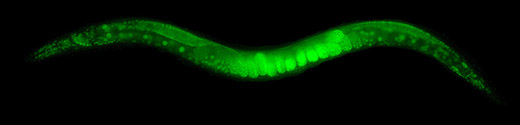

Neuro-muscular inspection is made through dyes as Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) and other dyes derived from calcium that allows to detect synaptic activity of a target as well as muscular contraction and relaxation that are neuronally activated [1][2]. These dyes are used and have been used in many trascendent studies as genetic markers [3].

Figure 1: C. elegans GFP Fluorescence

As to lipids studies is concerned, C. elegans has emerged as a significant obesity model.

Many studies use dyes as Nile Red, Sudan Black, or BODIPY to identify fat storage [4]. When mixed with the nematodes food, the E. coli bacteria, Red Nile and BODIPY dye multiple spheric celular structures in C. elegans’ instestine. However other studies have shown that, in the previous described conditions, the organelles related to the lisosomes dyed by Nile Red and BODIPY are not the only fat accumulation. Most of it is located in a different celular compartment that is not dyed by Nile Red, being Oil Red O the dye that allows for more precision and efficienc while locating the largest fat storages [5].

Figure 2: C. elegans Oil Red O Lipids Fluorescence [5]

It should be pointed out that fluorescence is not an exogenous phenomeno caused by external means. Instead the own C. elegans exhibits autofluorescence. In fact, a method of aging quantification of a C. elegans is the detection of intestinal autofluorescence [6]. In contrats, an individual death, natural or not, causes an intense blue autofluorescence [7].

References

[1] S. H. Chung, L. Sun, and C. V Gabel, “In vivo Neuronal Calcium Imaging in C. elegans,” J. Vis. Exp., no. 74, p. 50357, Apr. 2013.

[2] V. Venkatachalam et al., “Pan-neuronal imaging in roaming Caenorhabditis elegans,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 113, no. 8, pp. E1082–E1088, Feb. 2016.

[3] M. CHALFIE, Y. TU, G. EUSKIRCHEN, W. W. WARD, and D. C. PRASHER, “GREEN FLUORESCENT PROTEIN AS A MARKER FOR GENE-EXPRESSION,” Science (80-. )., vol. 263, no. 5148, pp. 802–805, Feb. 1994.

[4] K. Yen, T. T. Le, A. Bansal, S. D. Narasimhan, J.-X. Cheng, and H. A. Tissenbaum, “A Comparative Study of Fat Storage Quantitation in Nematode Caenorhabditis elegans Using Label and Label-Free Methods,” PLoS One, vol. 5, no. 9, pp. 1–10, 2010.

[5] E. J. O’Rourke, A. A. Soukas, C. E. Carr, and G. Ruvkun, “C. elegans Major Fats Are Stored in Vesicles Distinct from Lysosome-Related Organelles,” CELL Metab., vol. 10, no. 5, pp. 430–435, Nov. 2009.

[6] Z. Pincus, T. C. Mazer, and F. J. Slack, “Autofluorescence as a measure of senescence in C. elegans: look to red, not blue or green,” AGING-US, vol. 8, no. 5, pp. 889–898, May 2016.

[7] C. Coburn and D. Gems, “The mysterious case of the C. elegans gut granule: death fluorescence, anthranilic acid and the kynurenine pathway,” Front. Genet., vol. 4, p. 151, Aug. 2013.